What is a Pitch Deck? Meaning, Example, and Guide

This article will help you understand the concepts and components of an effective pitch deck.

Throughout many years of helping startup founders navigate fundraising, we've come across many pitch decks. We can confidently say that we know a thing or two about writing good pitch decks. In this article, we'll do a deep dive into the definition of a pitch deck and what the ideal pitch deck looks like.

Pitch Deck: What is It?

A pitch deck is a short and concise presentation, usually created using PowerPoint, Keynote, or similar software, used to provide your audience with a quick overview of your business plan. It typically covers key aspects such as your company's mission, business model, market opportunity, product or service, competitive landscape, financials, and team. The goal of a pitch deck is to attract investment by convincing potential investors of the viability and future growth of your business. Most pitch decks are around 15-24 slides long and are used during meetings with investors, demo days, or as a part of the initial screening process by accelerators.

A pitch deck shouldn't be a boring business presentation. It's a narrative that tells your company's story. Depending on your stage and your particular journey, this ‘story' can take different angles: solving a pressing problem, a unique business model, remarkable traction, revolutionary tech, or superhuman founders. Usually, a deck will have between 15-24 slides, but this depends on all the above factors and shouldn't be taken as a rule of thumb. The deck's goal is clear: you need to persuade your investor audience to trust you and your solution so they want to invest their money in your company.

A pitch deck can be used for different purposes, such as emailing it to help you land investor meetings, pitching, and presenting in front of an audience. Depending on these scenarios and time constraints, the presentation can have more or less information, but the structure should generally be the same.

In short: a pitch deck is a quick presentation that outlines your company's business plan to potential investors. The goals of a pitch deck vary, though generally it aims to secure financing from investors, or at least further conversations about investing in your startup.

When will you need a pitch deck?

You'll need a pitch deck throughout your journey as a founder and many stages of a startup's life. For starters, almost every U.S. accelerator program will ask for a pitch deck during their initial screening process. Once you're in, get ready for the "pitch practices." These spaces allow you to rehearse your pitch and refine your presenting skills. Rehearsing is crucial; it's designed to prepare you for future demo days. An event where you present your business to a room full of key players think investors and other program coordinators.

However, this is not the most common use of your deck. The most common use for a pitch deck is whenever you and your team decide it's time to seek external capital. Think of your pitch deck as your ‘presentation card.' Often, what will determine whether you can sit in front of potential investors is if your deck has a clear and compelling story that can be understood. The presentation decks can also serve as a pre-meeting brief, allowing investors a sneak peek before a face-to-face conversation, or as a discussion tool during your meetings to walk them through your value proposition clearly and concisely.

A pitch deck serves a dual purpose: not only does it provide investors with an overview of your company, making it easier for them to evaluate the investment potential, but it also helps you, as a founder, as a mental exercise into articulating the key aspects of your startup and pen key information and data about your company.

The ideal structure

Again, think of your deck as a story/journey your reader is going through. Throughout the presentation, the key questions the pitch needs to answer are:

- What market opportunity have you discovered?

- What have you built to tackle it? How does it work, and who is it for?

- How much are you growing, and will you continue to grow?

- And why are YOU and your team THE right ones to change that status quo?

These four guiding questions will frame the structure of your pitch deck First, you want to set the stage with your deck's introduction. This encompasses the cover slide and the status quo section. What's the current landscape, and what isn't working?

Next, we pivot to introduce your solution think of it as the story's hero. This is where the narrative takes a turn. We focus on what sets your solution apart, its features, how it generates revenue, and its target audience.

For seasoned entrepreneurs, this is also the point where we'd highlight any traction gained, demonstrating your understanding of your business's growth trajectory and your concrete plans for expansion.

Then, it's time to size up the market. You should explore how the target market responds and how big it is the stakes couldn't be higher. But that's not all; your audience will also be eager to learn about the competitive landscape and how you are better than your competitors.

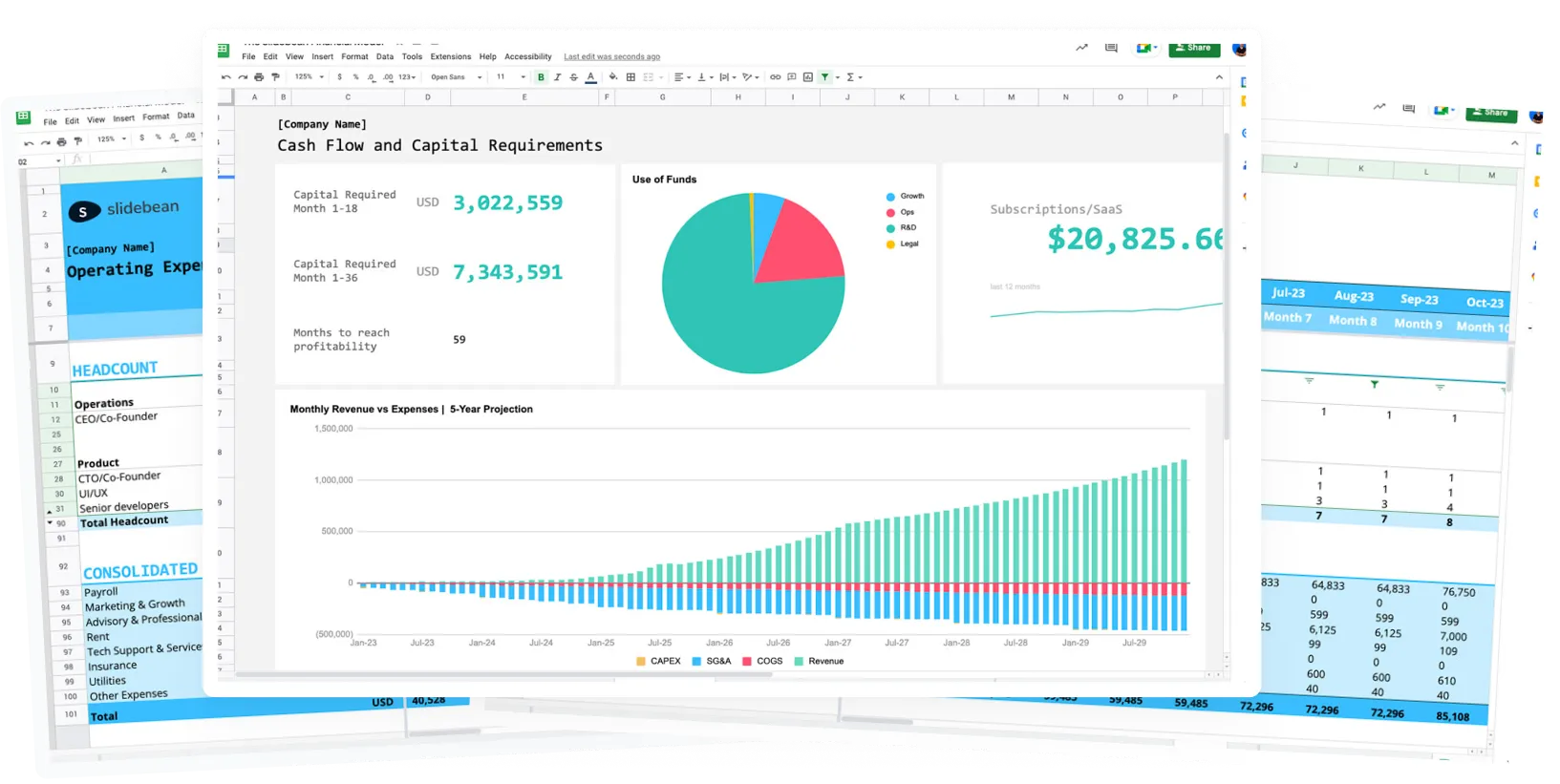

Finally, we reach the climax of the pitch deck. Here we highlight the founding team, your unique competitive edges, or perhaps your innovative rollout strategy. We wrap up this section by clearly outlining your funding needs and providing a breakdown of how the capital will be used.

What should be in a Pitch Deck Presentation?

Many authors, venture capitalists, startup founders, and evangelists have developed various iterations of what they believe are the essential components for successful pitch presentations. There is definitely not one correct answer. However, there are certain best practices and highly recommended components the deck should have.

At Slidebean, we've created this visual to show how we visualize the ideal story arc of a pitch deck.

This fits perfectly into the ideal pitch deck structure we tend to use at Slidebean.

-min.webp)

Debunking Pitch Deck Myths

As CEOs and founders approach their pitch decks they’ll inevitably come across some myths: like the number of slides they are allowed to use, or whether or not to include an advisors slide. Let me tell you right now, it’s all crap.

In the end a pitch deck is a summary of your company story, nothing more, nothing less. If your company story is long, and it takes you 25 slides to cover it, great. If you can do it in 10 without leaving anything out, better.

To me a pitch deck is this blend of storytelling, of building up excitement; with business, and numbers, and a very rational, cold decision which is: will this company make me, investor, money?

Does Your Company Really Need a Pitch Deck?

Companies come in all shapes and sizes, but only a handful of them are venture-fundable.

You may hear talk on the startup press about this and that company raising millions of dollars, but for the most part, these are fast-growth, massively SCALABLE companies, and that’s why they can (and must) raise capital to expand.

There’s really no terminology to tell them apart, but I like to use Startups vs. Small Businesses.

Yes, if we are strict about their definitions, all Startups begin as Small Businesses, but the difference I want to make here relates to their scale.

So let’s draw a line here and paint that picture.

Small Businesses

Say a developer and a UI designer got tired of their day jobs. They’ve built a name and a portfolio for themselves and they decide to start their agency.

To me, this is the definition of this category of ‘small business’. This is, by all means, a tech company, but in order to scale they will need to hire more and more designers and developers. Their margins, the profit the company makes after covering expenses, will always be limited because they are essentially selling man-hours.

Can they reach great scale? They can build an agency with 1,000 engineers, but that is a long-shot. Examples here are the McKisneys and th EYs of the world: massive consulting companies that still sell mostly, services; but those are exceptions.

Can they raise venture capital? Unlikely. And definitely not at the idea or early revenue stage.

Those companies are usually formed by 2 or 3 partners who bring in some capital of their own to get started. One of those partners might even be an ‘executive’ co-founder: while the other, or others bring the expertise and the work, the executive co-founder brings the capital.

But that is not an investor that you find with a pitch deck. It’s probably a relationship that you’ve already built, and that trust you to get in bed with you for this business.

There’s nothing wrong with being a ‘small business’ type of company. The US economy was built on these small businesses.

The Tech Startup

This is the company that you read about on Techcrunch. A company that has found a transformative market opportunity, and that is using technology to solve it in an extremely scalable way.

Uber is not a car or a taxi company. It doesn’t need to hire drivers. It operates all over the world and can open an operation in a city with 3 employees, because they are a marketplace. They are connecting drivers to riders.

Same with Airbnb. They don’t need to buy homes or rooms (like a hotel), they are just connecting the players in this economy.

Going to Social Media, when Facebook acquired Instagram in 2013, they were bought out for $1 Billion. The company had 250 million users and 13 employees. Because software is infinitely scalable, and you don’t need a massive staff to support it.

That’s the concept that I like to classify as a tech startup. Once again, technically, the development shop is a tech startup, but I’m not using the dictionary definition.

The story on how these companies fund their operation is very different. These are companies reaching for the moon, so they will need to raise capital every couple of years (assuming they are doing well).

On a SaaS (software as a service) for example, it’s expected that the founders build a prototype and sell it to a few customers before considering outside capital.

On a Social Media platform, fast user growth is expected before raising significant capital. Look at the Facebook story- assuming that you saw the movie: Thiel only invested in ‘The Facebook’ AFTER it was a hit in Harvard.

Other industries like Healthtech and Hardware do require capital earlier on, because they are very capital intensive just to get started.

For the most part, these companies will operate at a loss for years, because everyone is betting on the large play. Think Amazon, who didn’t turn a profit for decades, but today, it completely dominates the e-commerce industry. And AWS. And streaming.

Parts of a Pitch Deck

The Three-Act Structure

Rules are made to be broken, but I believe this structure is truly the ideal one. For this outline we combined our own experience, our analysis of hundreds of decks, from successful companies like Airbnb and Uber and finally, storytelling.

And let me start with that one, because as irrelevant, and unrelated as it may seem- storytelling makes or breaks a deck.

Who doesn’t love a good story- a story of how this team used their wits to overcome difficulties. Or a story on how everything stacked against them, and they won by the skin of their teeth.

I learned this stuff in film school, and it ruined movies a little bit for me, but most stories, films included, follow a 3-Act structure that looks like this.

During Act I, the SETUP, we have an introduction to the characters and to the status quo. We are presented with a universe that we can believe in, that we can invest in, as long as it’s realistic, and consistent with our own experience.

Then comes Plot Point 1, around a third of the movie in. This is a point in the movie where the story takes an unexpected turn, and the plot gets its direction changed.

In The Social Network, it’s when this coding, viral platform genius that we’ve been introduced to, gets presented with the Havard Connect idea by the Winkelvosses, and decides to steal it.

The first plot point also opens a range of possibilities of where the story could go. As viewers, we are at the mercy of the script and often have no idea where the conflict will go.

As the Plot changes direction, stakes start getting higher. We care about these characters and build excitement. This all builds up to the climax of the story, which comes right after the second plot point.

In the Social Network, the Second Plot point is Eduardo freezing the Facebook account: it’s another unexpected turn in the story. Instead of opening possibilities of where the story could go, it narrows them down. This is followed by the climax of the story, the confrontation between Mark and Eduardo in the Facebook office.

Try placing your pitch deck story in this arc.

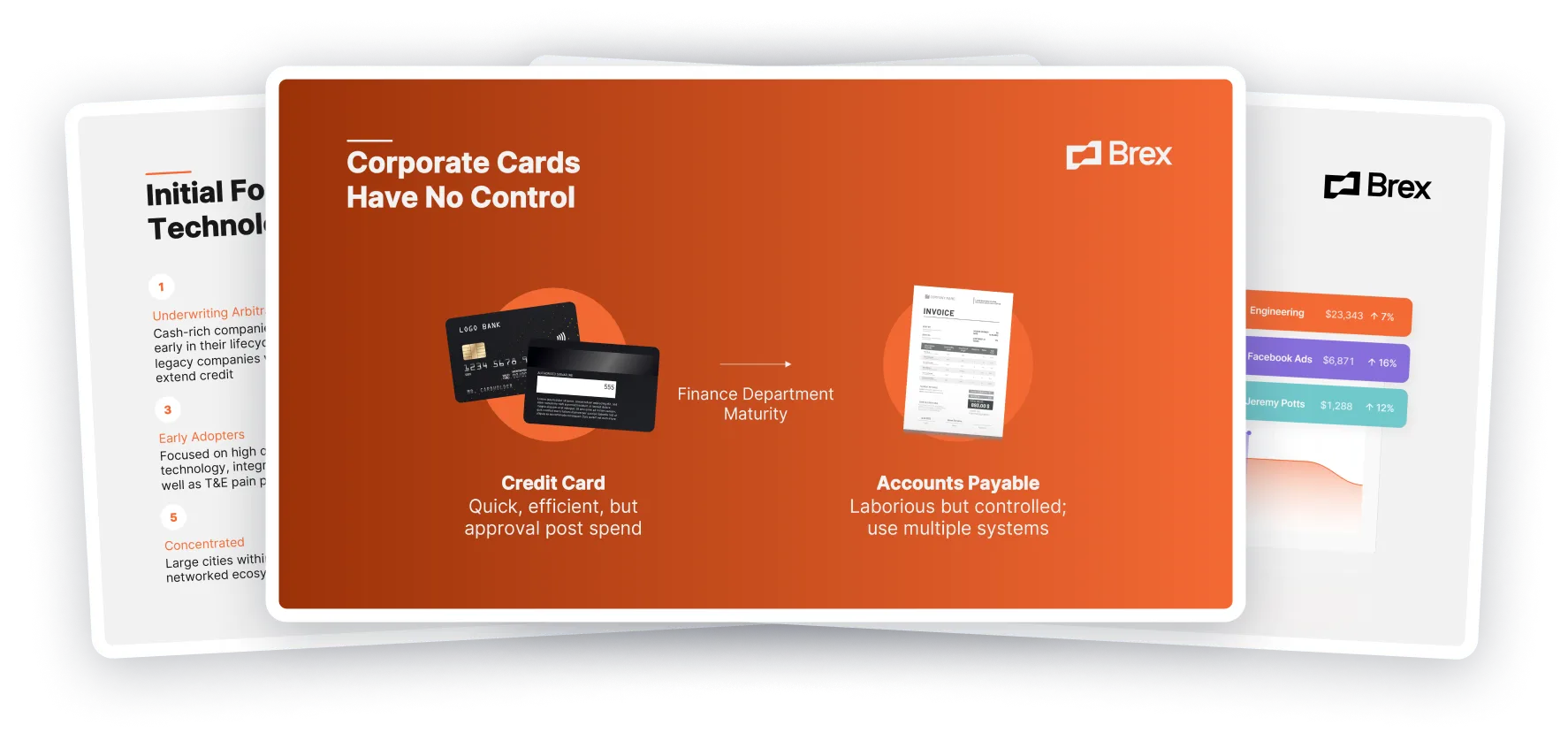

We start with an introduction, the status quo. What’s going on, how does the world operate today? What are the flaws?

Your Solution slide is the first Plot point. You are pivoting the direction of the story, of the current status quo and possibilities are endless.

Now you start narrowing down. The product takes shape. Stakes get higher. We understand the hero of the story, the product.

The second plot point and climax could vary depending on your business. Maybe it’s in your traction slides, because you tapped into an incredible distribution channel.

Maybe the plot twist revolves around the competitors, and how they foolishly overlooked something your team knows. Maybe it’s about your team, your background, and experience which is unmatchable.

It’s at that climax when the viewer is most vulnerable. It’s after that climax, that you get to ask for money.

Very broadly speaking, the key elements that fit this structure are listed below. This doesn't mean the deck should have no more than 13 slides. Depending on your particular case, many of these sections should be expanded into more than 1 slide.

- Problem

- Market Overview

- Solution

- Product/Features

- Audience

- Revenue Model

- Roadmap

- Traction

- Go-To-Market

- Market Size

- Competition

- Team

- Fundraising/Use of Funds

These core sections of a pitch deck are intentionally designed to flow from broad to detailed, starting with the business opportunity and gradually zooming in on why this particular company is poised to fill a gap in the target market.

If you're on the hunt for some pitch deck inspiration, check our gallery of successful pitch deck templates right here I want to take a moment to re-emphasize that this structure is, by no means, a rule of thumb. Every company has its own story, and whoever is creating the pitch deck will adapt these slides into the order that produces the best possible story, given their strengths. Early-stage startups, who usually don't have relevant traction, lean heavily on the problem-solution fit, the market potential, and being first to market. More mature companies, in contrast, tend to emphasize their traction, KPIs, unit economics, and how additional funding can accelerate their growth.

Regardless of the size of the company or the milestones to date, the ultimate goal of a pitch presentation is to provide a broad overview of how the startup works, its strengths, and future growth opportunities.

Are there different types of pitch decks?

The term pitch deck is broad. I’ve seen it used to refer to a sales deck. You could even use it to refer to a movie pitch.

As you’ve probably noticed, our expertise is on investor pitch decks.

More than different decks per se, the main factor to consider is that there are different scenarios in which you'll use a deck, so we definitely need to adjust the narrative to fit these different time constraints and content requirements. While there's no one-size-fits-all guide to the types of pitch decks, here are some commonly encountered decks:

Elevator pitch deck:

This is a deck that should, as the name suggests, be able to deliver a pitch for 1-2 minutes during an elevator ride with a potential investor - figuratively speaking. Nonetheless, these sorts of decks are highly condensed versions of your pitch. Focus on the most essential information: problem, solution, traction, market, use of funds, and growth.

Demo day pitch deck:

Usually a bit more detailed than an elevator pitch but still on the shorter side. These pitch decks are common on demo days when many startups present sequentially, and the time limit is sacred. Here, founders usually have no more than five minutes to present. These pitches are often presented in large auditoriums, and the focus is yourself, so the deck itself should have little-to-no-text and be heavy on visuals to capture your audience's attention.

Full investor meeting deck:

This is what you normally find when Googling “What is a Pitch Deck” or “Pitch Deck Meaning”. An investor meeting deck is the archetypical pitch deck and also the most commonly used. Typically, it showcases your company for potential investors to review and assess if it is venture-backable or not. This is a more in-depth look at your startup's aspects, from business model and go-to-market strategy to financial projections and fundraising needs. These decks have between 15-24 slides and are also called “email decks,” meaning they are sent to help you land investor meetings. They can also be used to guide in-person meetings and help you highlight traction and data that would otherwise be trickier to explain verbally.

Key components for a solid pitch deck

- Good Story Structure - Storytelling Arc: In pitch decks, the order in which you present your information is crucial almost as critical as the content itself. Your information should follow a logical order that paints an overall business picture and has a story arc that makes sense. Most storytelling techniques in public speaking also apply to narrating your business story.

- Easily Understandable: This point goes hand in hand with the structure and order of the deck and, honestly, is quite obvious. Readers need to understand your company and the deck, regardless of them being unfamiliar or unrelated to your industry. The typical trap in which many fall is getting too technical and using jargon that many of us simply - don't understand. Try to tell the story clearly, compellingly, and concisely so that anyone* can understand the deck and get excited about your company.

- Human-Centered & Relatable: It's tempting to focus too much on the solution you created and give lengthy explanations of your product's super cool features. The reality is that the best business idea is meaningless if it doesn't solve a genuine human problem. The deck needs to convey that there is a clear problem/solution fit. Make things relatable by providing proof of the user's pain points, quantify the problem, and mention how your solution improves their lives - and why your team is the only one that can do it. If your audience can't relate to the problem, convincing them of your solution will be hard.

- Compelling Visual Resources: While your presentation's content is vital, your slides' visual look is critical in engaging your audience. People get bored quickly, and a visually dynamic presentation can help you maintain their interest. We process images much more efficiently than text; use this to your advantage by crafting visually striking slides that enhance your message. And please, remember that this is not a business plan. You shouldn't have everything in your deck. This is a high-level document that has to paint a solid picture of your company. There will be a time and place to deep dive into different areas of the company; the slide deck is not the place.

- Traction-Oriented Slides: If you have the traction, brag about it. Results and actual data tend to be more relevant than anything else. They demonstrate you've found or started to find product/market fit, and that your addressable market has been identified and defined. Nothing gives you more credibility than actual, measurable success with paying customers. Bonus points: you must be prepared to discuss these metrics and unit economics once you present them, so make sure you know and understand them.

- A Healthy, Exponentially Growing Business: The simple (and hardest) truth of crafting a solid and compelling pitch deck is that it depends on your company's performance. Revenue-generating businesses, low-churning products, exponential and sustained growth, and consistent usage… these are the things that investors are looking for, and that will charm them. The reality behind the startup fundraising world is that investors want a 10x return for their investment. Despite the reputation of being risk-takers, they ultimately look for their investment to yield results.

A pitch presentation is valuable for founders and investors to assess collaboration opportunities. A solid deck can take you really far, and a deck full of red flags can deter you from even having the opportunity to pitch in person to potential investors. It is a good exercise because it forces you to do a conscious exercise to articulate your story in a compelling manner, as well as a format that is compatible with the majority of investors around the world. By no means is it an easy task, but the exercise of writing it will help you understand your company from an external perspective and force you to understand key aspects of the narrative you have: growth, metrics, solution, problem, etc.

I hope this article has clarified what a business deck is and the components of a 5-star deck.

For more insights, feel free to explore other articles on our blog about pitch deck basics.